Sigh, you didn't read it then.

7. How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: nutrition guidelines

7.1 Amount of protein

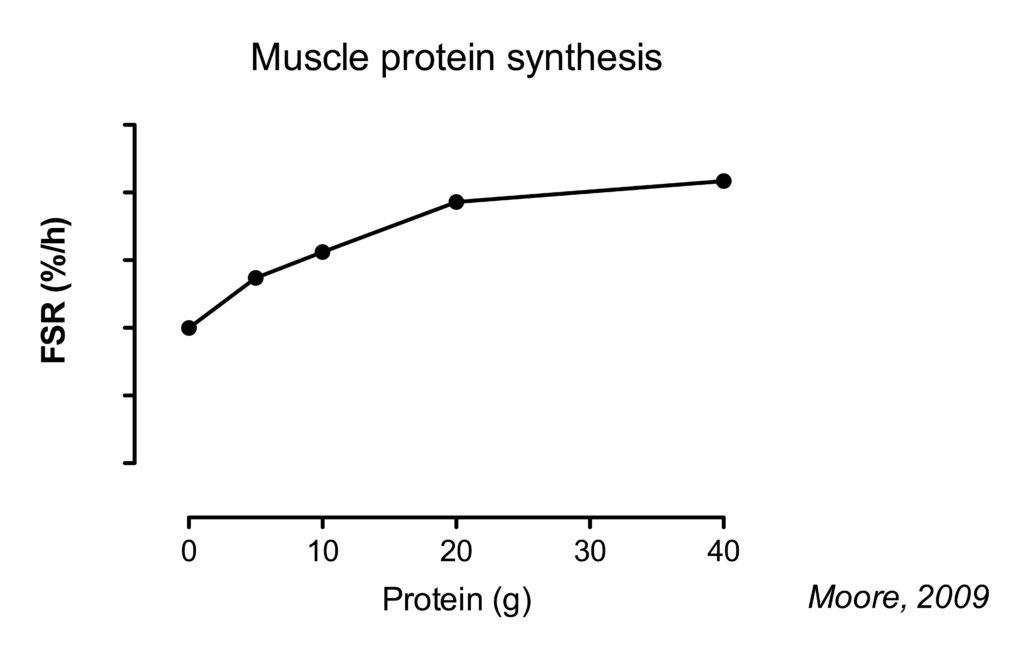

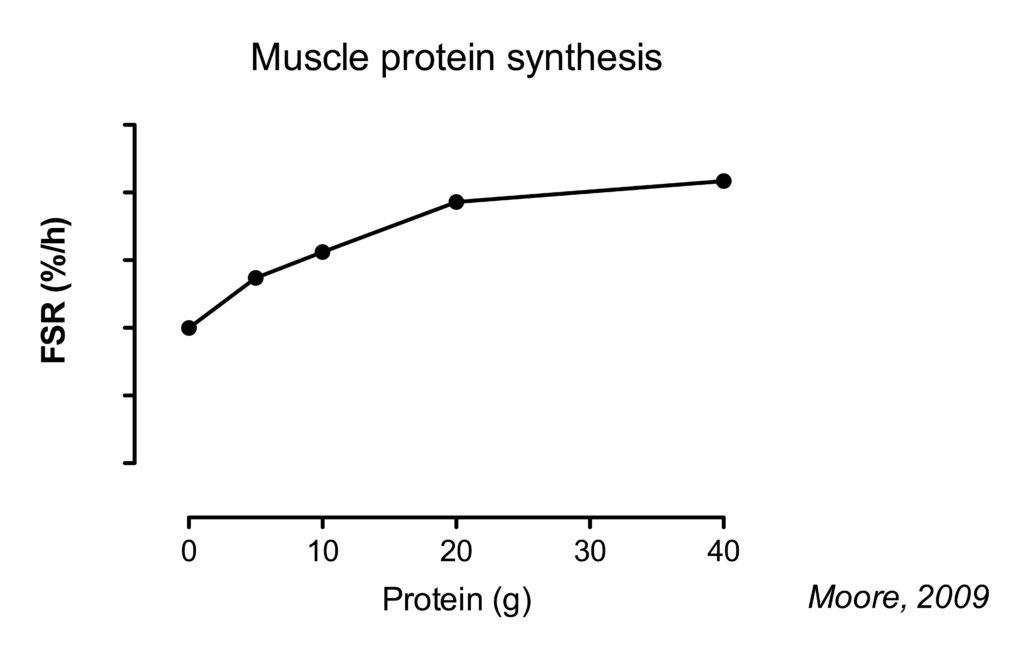

Twenty gram of protein gives a near-maximal increase in MPS after lower body resistance . Going up further to 40 g, results in a approximately 10% higher MPS rates

(Moore, 2009)(Witard, 2014).

When data of several studies was combined and the amount of protein was expressed per bodyweight, it was found that on average 0.25 g/kg would optimize muscle protein synthesis. However, the authors suggest a safety margin of 2 standard deviations to account for inter-intervidual variability, resulting in a dose of protein that would optimally stimulate MPS at an intake of 0.40 g/kg/meal.

More recently, it has been shown that the amount of lean body mass does not impact the response to protein ingestion

(Macnaughton, 2016). In other words: bigger dudes don’t need more protein to get the same response as smaller guys.

However, this study found that 40 g of protein resulted in approximately 20% higher higher MPS rates compared to 20 g. The authors speculated that this was related to the fact that this was following a session of whole-body resistance exercise compared to the lower-body exercise used in previous studies.

There is a linear increase in MPS rates up to approximately 20 g of protein. Further going up to 40 g gives an additional increase of 10-20%.

7.2 Protein source

Protein sources differ in their capacity to stimulate MPS. The main properties that determine the anabolic effect of protein are it’s digestion rate and it’s amino acid composition (particularly leucine).

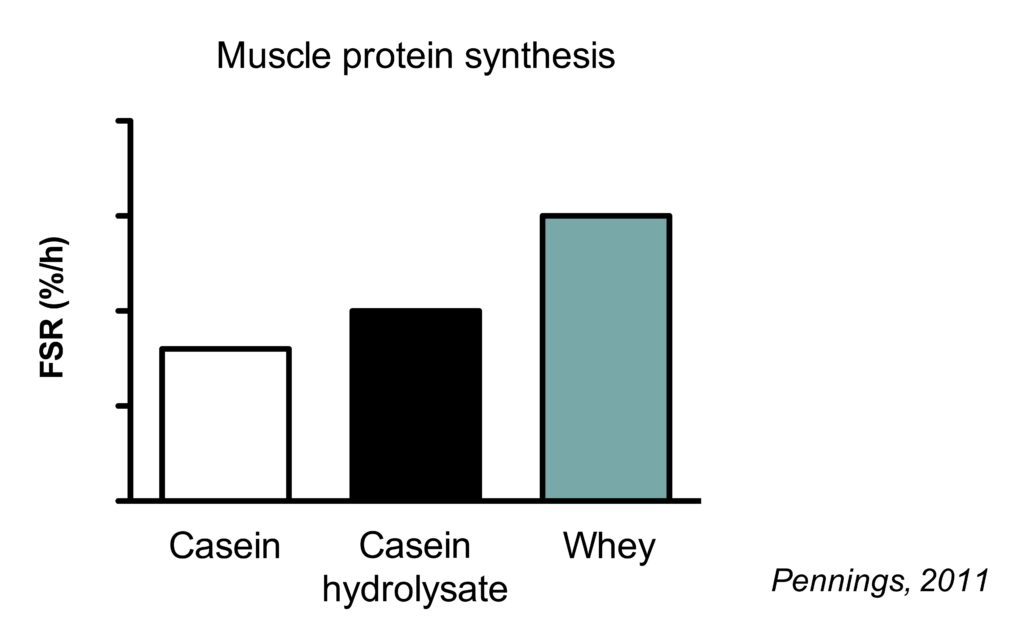

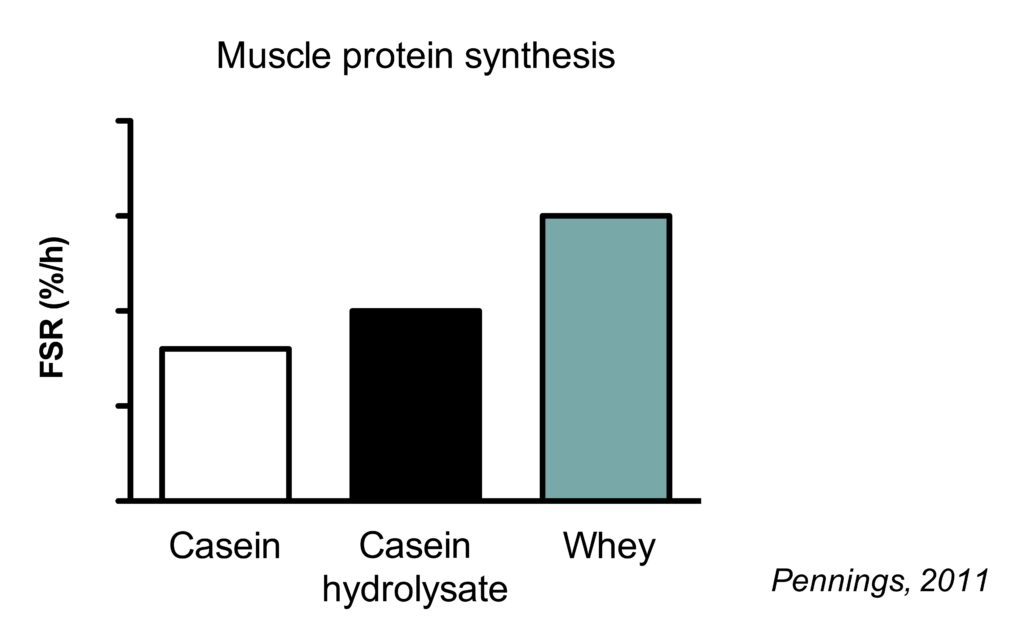

This is best illustrated by study which compared the muscle protein synthetic response to casein, casein hydrolysate and whey protein.

Casein is a slowly digesting protein. When intact casein is hydrolysed (chemically cut into smaller smaller pieces), it resembles the digestion of a fast digesting protein. Consequently, hydrolyzed whey results higher MPS rates than intact casein.

However, the muscle protein synthetic response to hydrolyzed is lower than that of whey protein. While both proteins are fast digesting, whey protein has a higher essential amino acid content (including leucine)

(Pennings, 2011).

Animal based protein sources are typically have a high essential amino acid content and appears more potent than plant protein to stimulate MPS

(Van Vliet, 2015). However, there this can potentially compensated by ingesting a greater amount of plant protein

(Gorissen, 2016).

The protein digestion speed and amino acid content (particularly leucine) are the main properties that determine the anabolic effect.

7.3 Leucine

Leucine is the amino acid that is thought to be most potent at stimulating MPS. Peak plasma leucine concentrations following protein ingestion typically correlate with muscle protein synthesis rates

(Pennings, 2011). This supports the notion that protein digestion rate and protein leucine content are important predictors for anabolic effect of a protein source.

While leucine is very important, other amino acids also play a role,

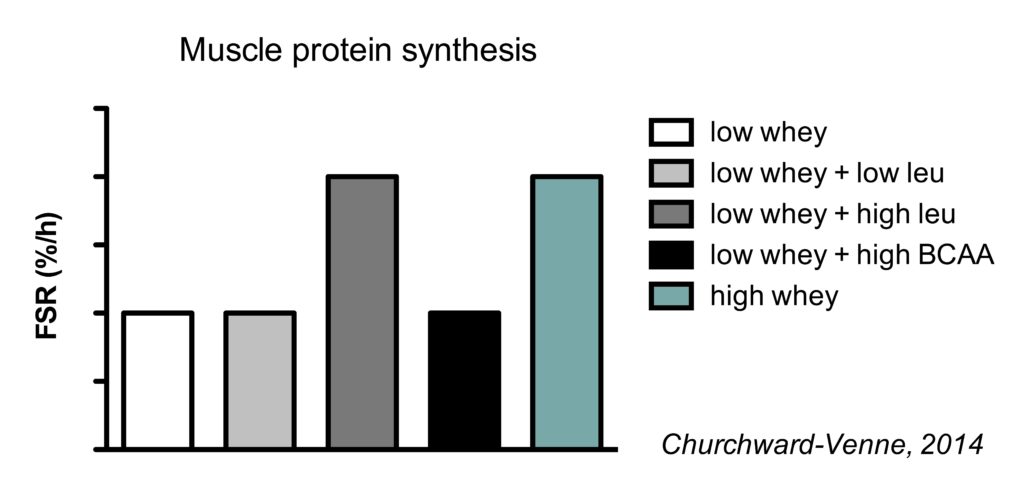

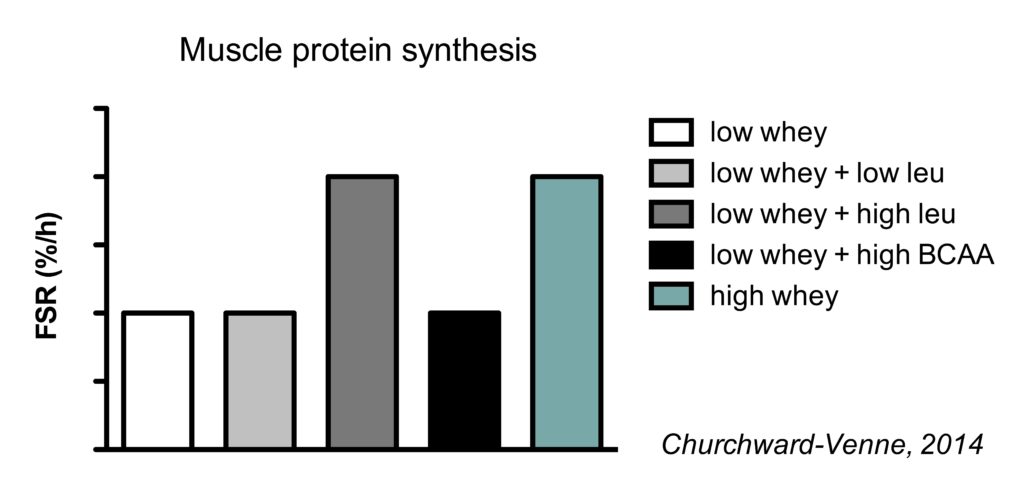

This is best illustrated by study which compared the muscle protein synthetic response to five different supplemental protocol:

- 6.25 g whey

- 6.25 g whey with 2.25 g leucine for a total of 3 g leucine

- 6.25 g whey with 4.25 g leucine added for a total of 5 g leucine

- 6.25 g whey with 6 g BCAA added (4.25 g leucine, 1.38 g isoluecine for, and 1.35 g valine)

- 25 g whey (contains a total of 3 g leucine)

All five conditions increased muscle protein synthesis rates compared to fasting conditions. As expected from our earlier discussion on the optimal amount of protein, 25 gram of protein increased MPS rates more than just 6.25 gram.

Interestingly, the addition of 2.25 gram leucine to 6.25 gram whey did not further improve MPS. Since this low whey + low leucine amount had the total amount of leucine as 25 g whey (which contains 3 g leucine), it indicates that leucine alone doesn’t determine the muscle protein synthesis response.

The addition of a larger amount of leucine (4.25 gram) to the 6.25 gram whey did further improve MPS, with MPS rates being similar to the 25 gram of whey. This indicates that a the addition of a relatively small amount of leucine to a low dose of protein, can be as effective as a much larger larger total amount of protein.

Finally, it’s really interesting that the addition of the 2 other branched chain amino acids (BCAA) appeared to prevent the positie effect of leucine on MPS. Isoleucine and valine use the same transporter for uptake in the gut as leucine. Therefore, it is speculated that isoleucine and valine compete for uptake with leucine, resulting in a less rapid leucine peak which is thought to be an important determinant of MPS rates.

The leucine content of a meal is an important determinant of the anabolic to that meal. Suboptimal amounts of protein can be supplemented with leucine to improve the muscle protein synthetic response.

7.4 Carbohydrate or fat co-ingestion

Carbohydrates slows down protein digestion, but have no effect on MPS

(Gorissen, 2014). In agreement, adding large amounts of carbohydrates to protein does not improve post-exercise MPS rates

(Koopman, 2007).

In addition to the effects on protein digestion, it has been suggested that carbohydrate stimulate insulin release, which may stimulate muscle protein synthesis and/or muscle protein breakdown rates. However, the addition of carbohydrates to post-exercise protein has no effect on muscle protein synthesis or breakdown rates. The effects on insulin on muscle protein breakdown rates are described in more detail in section 2, and the effects of insulin on muscle protein synthesis are further described in section 7.6.

Adding oil to protein does not slow down protein digestion or MPS

(Gorissen, 2015). It possible that oil simply floats on top of a protein shake in the stomach, and that a solid fat would delay digestion. One study has reported a greater increase in net muscle balance following full-fat milk compared to fat-free milk (although this study used the 2 pool arterio-venous model which is not the most reliable measurement).

Carbohydrate co-ingestion delays protein digestion, but has not effect on muscle protein synthesis or muscle protein breakdown rates. Fat co-ingestion has received little attention, but is unlikely to have a large impact on muscle protein synthesis.

7.5 Whole food and mixed meals

Most research has looked at isolated protein supplements in liquid form such as whey and casein shakes.

Thirty gram protein provided in the form of 113 gram 90% lean grounded beef results in a similar MPS response as 90 gram protein (340 gram beef). This supports the protein dose-response relationship observed with protein supplements where 20 g of protein gives a near maximal increase in MPS.

Minced beef is more rapidly digested than beef steak, indicating that food texture impacts protein digestion. However, there was no difference in MPS between these protein sources.

Beef protein is more rapidly digested than milk protein. However, milk protein stimulated MPS more than beef in the 2 hours. Between 2 and 5 hours, there was no significant difference between the sources. This indicates that digestion speed not always predict the muscle protein synthetic response of a protein source.

As discussed in the previous section, the addition of carbohydrate powder or oil to a liquid protein shake does not impact muscle protein synthesis. However, it is unknown how the components of (large) mixed meals interact. For example, the addition whole-foods carbohydrates such rice, patato’s, or bread to whole-food protein sources such as chicken.

It can be speculated that the protein in mixed meals is less rapidly digested, which is typically (but not certainly not always) associated with a lower increase in MPS.

Whole-foods can effectively stimulate muscle protein synthesis. Little is known about the muscle protein synthetic response to large mixed meals consisting of whole-food protein, carbohydrate and fat sources.

7.6 Insulin

As described in my systematic review, insulin does not stimulate MPS

(Trommelen, 2015).

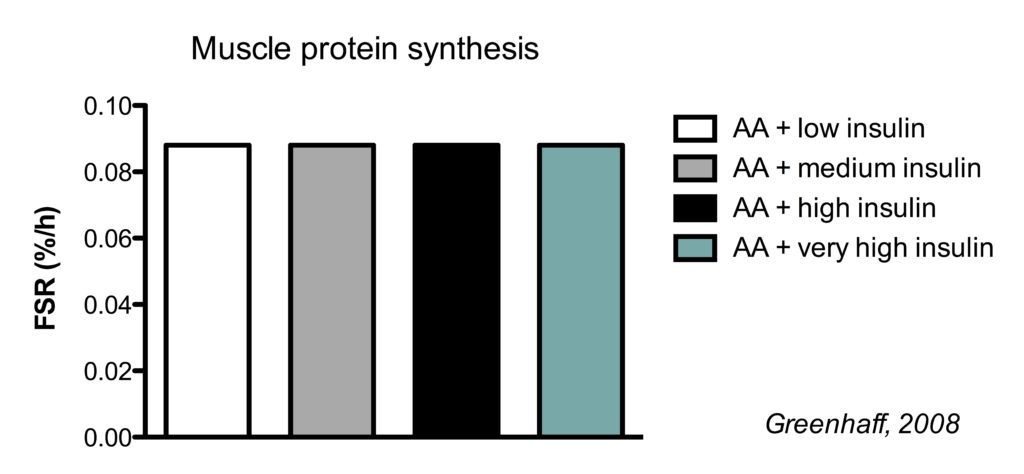

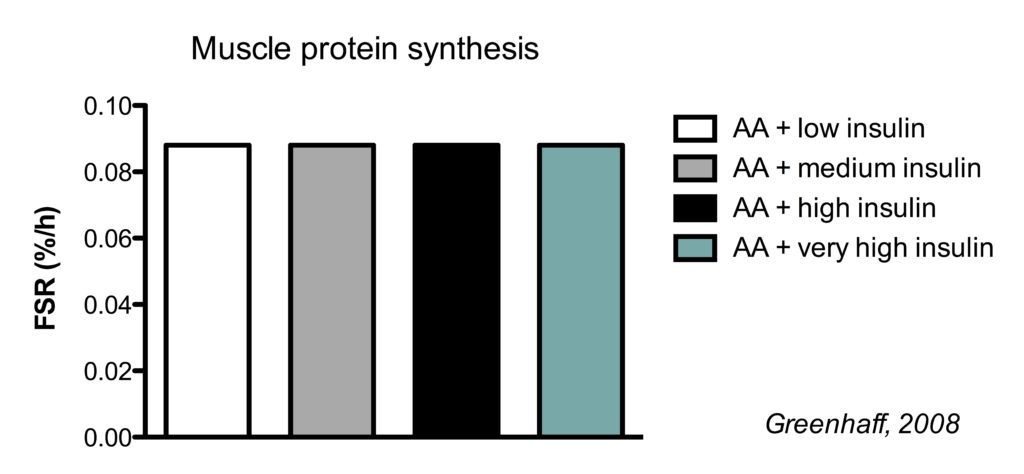

This is best illustrated by study which clamped (maintained) insulin at different concentrations and also clamped amino acids at a high concentration.

There were four conditions:

- high amino acids + low insulin

- high amino acids + medium insulin

- high amino acids + high high insulin

- high amino acids + very high insulin

In the illustration below, you see the effects on muscle protein synthesis.

Regardless whether insulin levels were kept low (similar to fasted levels) or very high, MPS rates were the same in all conditions.

In my systematic review, I describe the effect of insulin in other conditions including in the absence of amino acid infusion, but the conclusions remains that insulin does not stimulate MPS under normal conditions

(Trommelen, 2015). However, it should be noted that insulin stimulates MPS at at supraphysiological (above natural levels) doses

(Hillier, 1998). In the bodybuilding world, insulin is sometimes injected at supraphysiological doses to stimulate muscle growth.

Insulin inhibits muscle protein breakdown a bit, but only a little is needed for the maximal effect (this is discussed in dept in section XXX). A protein shake alone increases enough insulin to maximally inhibit muscle protein breakdown, you don’t need additional carbohydrates

(Staples, 2011).

Insulin does not stimulate muscle protein synthesis (unless injected at supraphysiological doses). Insulin inhibits muscle protein breakdown, but only a minimal amount of insulin is needed for the maximal effect.

7.7 Protein timing

Exercise improves the muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion. Therefore, it has been suggested that protein intake immediately post-exercise is more anabolic than protein ingestion at different time points.

Probably the best evidence to support the concept of protein timing is a study which showed that protein ingestion immediately after exercise was more effective than protein ingestion 3 h post-exercise (though this study used the 2 pool arterio-venous method which is not a great measurement of muscle protein synthesis)

(Levenhagen, 2001). In contrast, a different study observed no difference in MPS was found when essential amino acid were ingested 1 h or 3 h post-exercise

(Rasmussen, 200).

In addition, resistance exercise enhances the muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion for at least 24 hour

(Burd, 2011). It is certainly possible that the synergy between exercise and protein ingestion is the largest immediately post-exercise and then slowly declines in the next 24 h hour. However, these data suggest that there is not a limited window of opportunity during which protein is massively beneficial immediately post-exercise, that suddenly closes within a couple of hours.

Overal, no clear benefit to protein timing has been found in studies measuring muscle protein synthesis studies. As such studies are much more sensitive to detect potential anabolic effects compared to long-term studies measuring changes in muscle mass, it unlikely that long-term studies will observe benefits of protein timing.

In agreement, a meta-analysis concluded that protein supplementation ≤ 1 hour before and/or after resistance exercise improved muscle mass gains

(Schoenfeld, 2013). However, this effect was largely explained by the fact that the protein supplementation increased total protein intake, rather than the specific timing of protein intake.

From a practical perspective, a protein shake during or after a workout:

- is easy to do

- theoretically may have a very small benefit

- is a simple method to improve total protein intake

- prevents FOMO (fear of missing out on something)

So it could be argued: why not do it? It is mostly up to personal preference.

Evidence is lacking to support that protein ingestion around resistance-exercise is more effective than protein intake at other time points.

7.8 Protein distribution

An even balance of protein intake at breakfast, lunch and dinner stimulates MPS more effective than eating the majority of daily protein during the evening meal

(Marerow, 2014). Providing 20 g of protein every 3 hours stimulates MPS more than providing the same amount of protein in less regular doses (40 g every 6 hours), or more regular doses (10 g every 1.5 hour)

(Areta, 2013).

Muscle protein synthesis rates are not only determined by total protein intake, but also the pattern of protein intake.

7.9 Muscle full effect

The muscle full effect is the observation that amino acids stimulate MPS for a short period, after which there is a refractory period where the muscle does not respond to amino acids. More specifically, after protein intake, there is an lag period of approximately 45-90 min before MPS goes up and peaks between 90-120 minutes, after which MPS returns rapidly to baseline even if amino acid levels are still elevated

(Bohe, 2001)(Atherthon, 2010).

The muscle full effect has given birth to a theory on how to optimize protein intake throughout the day in the online fitness community. It suggests that after amino acids levels have been elevated, you should let them drop down back to fasting levels to sensitize the muscle to amino acids again. Subsequently, protein intake will stimulate MPS again.

There is no evidence to support this theory.

The suggested mechanism seems unlikely as many food patterns results in elevated amino acid levels throughout the whole day. The traditional bodybuilding diet consists of very frequent, very high protein meals (e.g. chicken, rice, broccoli 6 times a day). In fact, it was specifically designed with the goal of keeping amino acids elevated throughout the whole day so there would always be enough building blocks for form new muscle tissue. Or intermittent fasting where all daily protein is eaten in a short time period (usually 8 hours).

These diets would only allow for a single ~90 min increase in MPS during a whole day. Clearly, that’s not what’s happening as these approaches are used by many with great success to to improve muscle mass.

More likely, there’s a refractory period and it simply takes some time before the muscle responds to AA again. You don’t have to let amino acids drop to sensitize the muscle.

However, the relevance of the muscle full effect can be questioned in athletes.

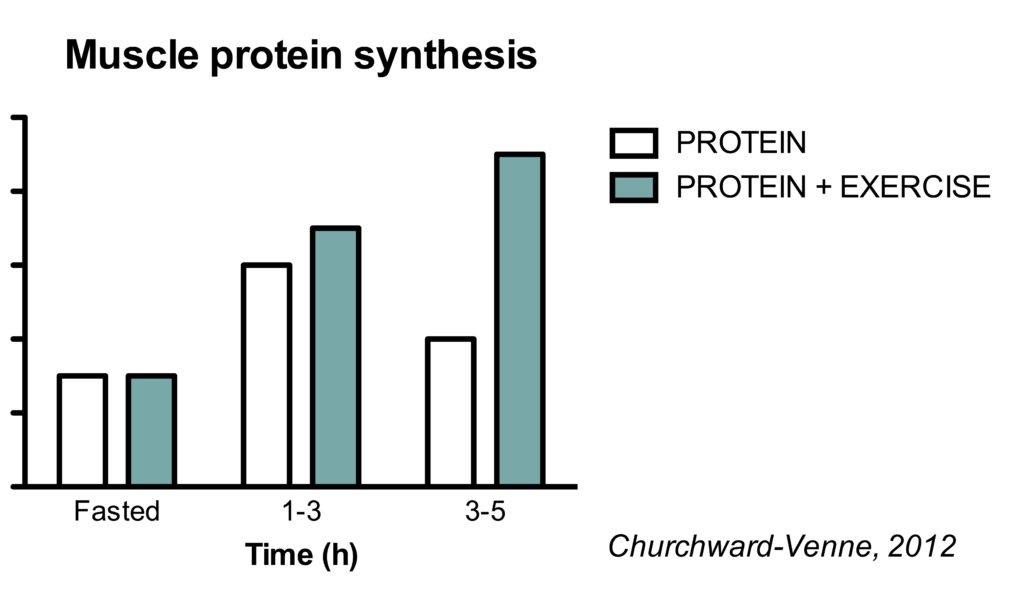

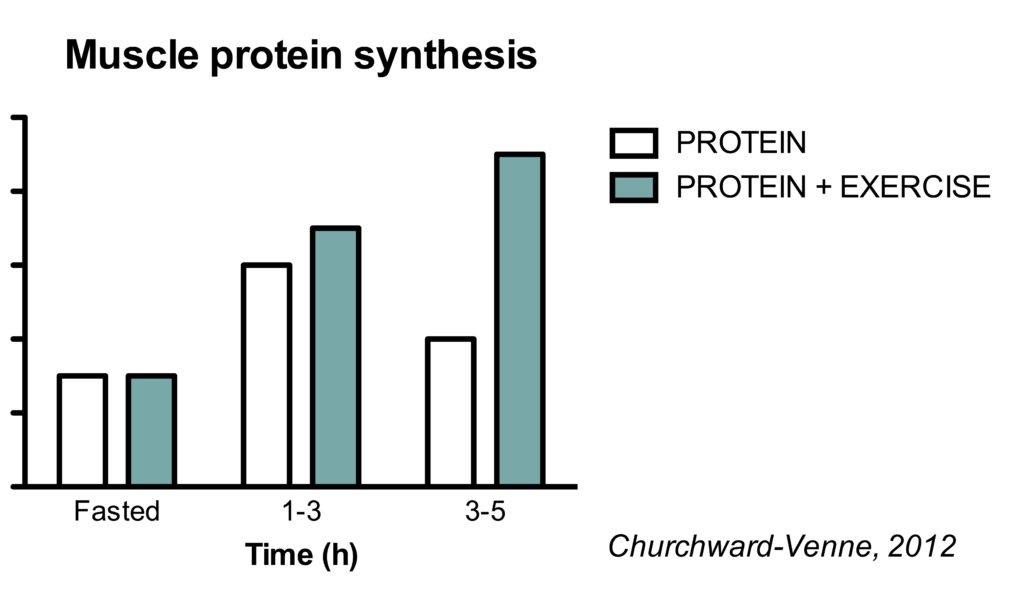

This is best illustrated in a study where the effect of protein was assessed in both rested and post-exercise conditions

(Churchward-Venne, 2012).

Protein intake alone stimulates MPS in the 1-3 h period after ingestion. Subsequently, MPS rates fall back to basal rates. However, in post-exercise condition, protein stimulated MPS rates in both the 1-3 h and the 3-5 h period.

It appears that the muscle full effect is not present in acute post-exercise conditions. It’s interesting to note that resistance exercise can increase the sensitivity of the muscle to protein for at least 24 h

(Burd, 2011).

The muscle full effect is an interesting phenomenon, but we don’t understand it well enough to let it influence our protein intake recommendations.

The muscle full effect is the observation that amino acids stimulate MPS for only a short period in a rested state, after which there is a refractory period where the muscle does not respond to amino acids.

7.10 Protein prior to sleep

As discussed above, an effective protein distribution optimizes MPS. Therefore, it makes sense to eat protein just prior to overnight sleep, the longest period you can’t eat. 40 g of protein prior to sleep increases MPS during overnight sleep

(Res, 2012). Protein supplementation (27.5 g) prior to sleep during a 12-week resistance training program improves muscle mass and strength gains

(Snijders, 2015).

Protein prior to sleep stimulates muscle protein synthesis during overnight sleep.

7.11 Energy intake

Only three days of dieting already reduce basal MPS

(Areta, 2014). This shows that an energy deficit is suboptimal for MPS, however you can grow muscle mass while losing fat

(Longland, 2016). It is unclear if eating above maintenance is needed to optimize MPS.

A negative energy balance decreased muscle protein synthesis rates. It’s not known if overeating (bulking) increases muscle protein synthesis.